Theology for theology sake is worthless. The reason we ponder the mysteries of the cosmos is so that we can live life better. Nowhere is this concept more applicable that when dealing with the great Sovereignty of God/Free Will dilemma.

To some, this dilemma is so huge and so crazy that they will walk away from it with their fingers in their ears. However I would say that we need to think about this issue for it affects how we act when sh*t happens in our lives. Pastors especially need to ponder this issue as they will be called upon by others in the middle of some sh*tty events and how they answer this question will color their interactions.

Over the last few weeks, I have talked about some alternatives to the typical Arminianism/Calvinism option given to folks. Namely I brief discussed Open Theism and the Eastern Orthodox’s consent and participation view of God’s rule. Today I’m going to try to think through how these views would color one’s interactions with folks who are in the middle of pain and suffering. In doing this, I fully note that I will most likely misrepresent one or more of these groups….and for that I will apologize in advance and ask for your help via the comment section below.

Calvinism

There are five major points within Calvinism that dictate how they view the world. These five points (also known as TULIP) are listed below:

- Total Depravity

- Unconditional Election

- Limited Atonement

- Irresistible Grace

- Perseverance of the Saints

Because of Calvinism’s position of Total Depravity (i.e. original sin; everyone is born a sinner), Irresistible Grace and Unconditional Election, Calvinist have the hardest position to defend when it comes to the problem of evil. Since God is in charge of everything (either directly or allowing it), the sh*t that happens to people is all part of God’s plan.

Therefore when a two-year old child is murdered, a Calvinist has to hold on to the belief that God caused/allowed it to happen for some reason (typically to teach someone something or because of some unknown ‘good’ reason which we human can never know). As a pastor and a Jesus follower, I think this mentality is harmful and does not draw people to Jesus. (yeah, I’m fairly biased against this viewpoint…) 😛

Arminianism

Arminianism, why held by a large portion of the Protestant church, isn’t always understood or acknowledged due to the vocal criticism of influential Calvinists. Roger Olson, a leading Arminian theologian, once described Arminianism has holding onto the following items (all words are his, I just split his sentence into bullet points):

- Total depravity (in the sense of helplessness to save himself or contribute meritoriously to his salvation such that a sinner is totally dependent on prevenient grace for even the first movement of the will toward God)

- Conditional election and predestination based on foreknowledge

- Universal atonement

- Grace is always resistible

- Affirms that God is in no way and by no means the author of sin and evil but affirms that these are only permitted by God’s consequent will.

The outworking of this view holds that that humanity can resist God’s grace and choose their own actions, which will sometimes lead to negative consequences for themselves and others. Arminianism also holds that while God has foreknowledge of the future without actually dictating and controlling the future. (Granted there are some Arminianism who hold a stronger view of God control things similar to their Calvinist cousin.)

Typically an Arminianist would say that God has two wills: antecedent and consequent. God’s antecedent will states that he wants everyone to be saved while his consequent will acknowledges that only those who believe will be saved (i.e. “God reluctantly permits sin and enables it” – to quote Olson).

This means that the sh*t that happens isn’t the divine will of God acting upon this world. Rather it is the consequences of sin, death, and evil being played out in a world with free agents (i.e. humanity). In the case of a two-year old being murdered, an Arminianism would comfort the parents with the knowledge that the death of their child was not in God’s plan. It was something contrary to the antecedent will of God that happened because of the sin, death, and evil in the world.

Open Theism

Open Theism

This view of Sovereignty of God is similar to Arminianism (in fact, Roger Olson considers it as a variation of Arminianism) in that highlights the free moral agents of humanity. As in, humans are free to make choices that may or may not be within line with God’s plan. The major difference between Open Theism and classic Arminianism is that Open Theism pushes the free will boundaries of humanity to the limits without going into Pelagianism (i.e. humanity still need God to rescue them from evil due to original sin).

In other words, an Open Theist would say that humanity has complete control over the future with God working within creation and with humanity to guide the overall direction of history towards his overarching conclusion. Because of this, the timeline of God’s plans can, and are, subject to change according to the actions of humanity. This is not to say that God’s plans and/or promises will fail to happen, rather it is the timing of those plans/promises that can be changed. Just like the people of Israel delayed God’s plan for them to go enter into the Promise Land by 40 years, so can we delay God’s plans/promises.

Accordingly, an Open Theist would respond to a young child’s murder similar to that of an Arminianism in that they would both hold that the death of the child was not something sanctioned by God. Rather it was the consequences of sin, death, and evil being played out in a world. Jesus, rather than saying away from this pain, is there in the middle of the pain, holding the family tight and walking with them through pain. At its root, Open Theism is a warfare worldview that sees the world through a lens of a spiritual battle between God and sin/death/evil/satan. This, I might add, doesn’t mean that Calvinism and Arminianism doesn’t contain a warfare mentality. Rather this is to say that Open Theism places this warfare view at the forefront of their worldview along with the free will of humanity.

Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodox

The Eastern Orthodox’s view of the Sovereignty of God is one of God’s consent and participation (as mentioned last time). This means that God consent (i.e. gives up his authority to rule) to natural law (gravity, weather patterns, etc.) and human freedom. However rather than walking away and letting things go, God also participates within creation to rescue us (i.e. Jesus).

In addition, Eastern Orthodox rejects the total depravity of humanity embraced by the other views. This may sound like a heresy to some of you as total depravity is something that has been drilled into Western Christianity to the point that it is taken for granted. However if you study church history, you will find that the concept of total depravity didn’t come into the church until St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430 AD).

The background of the concept being St. Augustine’s debate with Pelagius on whether or not humanity could save themselves without God’s help. St. Augustine held that all of humanity was sinful with each of us being condemned for Adam’s sin. This sin was passed down throughout the ages through the human seed – a view that helped get sex labeled as sinful rather than beautiful (i.e. sin was passed generationally through the father’s semen to their children). Because of the total depravity of humanity, we need God to rescue us. Pelagius, on the other hand, held that we were born good and could rescued ourselves. While the church at large (Western and Eastern) rejected Pelagius view of sin and salvation, the Western half (i.e. Roman Catholic and then Protestantism) adopt St. Augustine’s view of original sin and total depravity while the Eastern half of the church, now known as the Eastern Orthodox Churches, did not.

Instead the Eastern Orthodox Churches adopted the view that humanity is, and was, created in the image of God and is by nature pure and innocent. Sin, however, has entered into the world through Adam and Eve as a sickness that effects every generation. Bishop Kallistos Ware puts it this way in his book The Orthodox Way:

“Original sin is not to be interpreted in juridical or quasi-biological terms, as if it were some physical ‘taint’ of guilt, transmitted through sexual intercourse. This picture, which normally passes for the Augustinian view, is unacceptable to Orthodoxy. The doctrine of original sin means rather that we are born into an environment where it is easy to do evil and hard to do good; easy to hurt others, and hard to heal their wounds; easy to arouse men’s suspicions, and hard to win their trust. It means that we are each of us conditioned by the solidarity of the human race in its accumulated wrong-doing and wrong-thinking, and hence wrong-being. And to this accumulation of wrong we have ourselves added by our own deliberated acts of sin. The gulf grows wider and wider. No man is an island. We are ‘members one of another’ (Eph. 4:24), and so any action, performed by any member of the human race, inevitably affects all the other members of the human race. Even though we are not, in the strict sense, guilty of the sins of others, yet we are somehow always involved.”

I mention all this because when it comes dealing with the sh*t of this crazy, messed up world, it really helps to know that we, humanity, are made the image of God. This means that when God grants us the freedom to reject or accept him, we aren’t automatically going to reject him. Rather there is a part of us, no matter how buried or small, that desires to be close to our Creator King. Humanity was created to be in a loving relationship with God and being outside of that relationship is an unnatural state not a natural state.

Practically this means that a pastor or Jesus follower can comfort the parents of a murdered toddler with the understanding that not only is Jesus there within the pain, but that this child who died was loved and embraced by the Creator King. Yes, sh*t happened due to the war that ranges around us. Yet the pain wasn’t from the hand of God nor was it his will that allowed/created the pain. Rather Jesus loves the child and was/is with them/us – in pain and death.

Fr. Emmanuel Clapsis puts it this way:

“We should not try to explain suffering or construct theories about the reasons for suffering in the world and systematic explanations that seek to reconcile innocent suffering with belief in a good and all powerful God. The pervading presence of senseless suffering in the world falls outside the bounds of every rational system. Remember how Dostoyevsky in his book Brothers Karamazov was seized with horror in contemplating the picture of suffering throughout the world, especially the suffering of the innocent and of the little children. The only answer, which Aliosha (representing Dostoyevsky’s own faith and attitude) can give is the image of the Crucified: He can pardon all; He can reconcile all, for He has measured the depth of our afflictions, of our loneliness, and of our pain. In the Crucified Christ, God does not remain a distant spectator of the undeserving suffering of the innocent but He participates in their suffering through the Cross and plants hope in the life of all afflicted persons through the Resurrection. When faced with the mystery of evil and suffering, the story of Jesus as the story of God is the only adequate response. The human quest for meaning and hope in tragic situations of affliction, draw from Christ’s death and Resurrection the power of life needed for sustenance. Thus, as Christians we do not argue against suffering, but tell a story…”

“God does not intervene to save Jesus, but neither does God abandon Jesus. Jesus’ life ends with an open question to God, “God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” God answers to the crucified Jesus by raising Him from the dead and glorifying Him. The resurrection signifies that God is present in the suffering of Jesus and of every human person. If we speak of Jesus’ real abandonment by God at Calvary, this could lead to the mistaken impression that suffering human beings are also forsaken by God. Instead, we must speak of God as silently present to Jesus at this terrifying moment, just as God is silently present to all those who suffer. This silent presence of God to Jesus becomes manifest in the Resurrection. The resurrection of Jesus confirms and completes all that Jesus was about in His life. The bottom line of the Christian faith is that God will be victorious over evil and suffering, as exhibited and effected in the death and resurrection of Jesus.” (emphasis added)

Conclusion

Throughout this post, I have sought to highlight how one’s view on the Sovereignty of God affects how one interacts with pain and suffering. I know that I most likely left out bits and pieces of this view or that. Yet my goal wasn’t to detailed out everything; rather I was trying to give you all a taste of what each view looked like. At the end of the day there are great Jesus followers who hold to all these views and I would gladly worship the Living King with them!

However I must also admit that when it comes down to pastoring and dealing with people in the trenches, I would rather deal with someone who hold to an Eastern Orthodox, Open Theism or Arminianism view of the Sovereignty of God. Calvinism, as I understand it, just doesn’t lend itself very well to compassion and mercy… so yeah, sorry my 5-point friends. :/

I would also say that on a personal level, I am leaning more and more towards the Eastern Orthodox view of consent and participation (as if that was’t obvious!). There is just something there that I love. Something that fits well with the mystery of the here and not yet that I see throughout the Scripture. Good stuff worth pondering. 😀

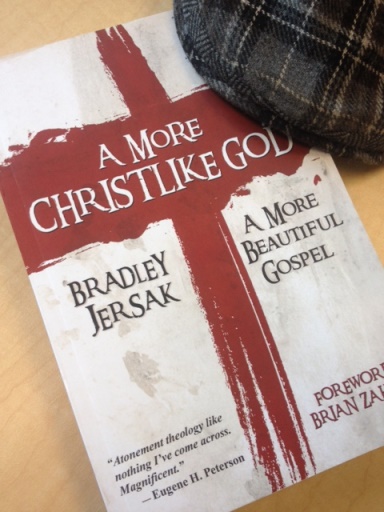

I read it twice. Within three months.

I read it twice. Within three months. Connected with the sovereignty of God and human participation topic are the issues of the atonement (i.e. what happened on the cross?) and the wrath of God. While anyone of these topics could have been a book within itself, Brad seamlessly weaves all three issues into his book while keeping the focus on Jesus and the cruciform God. I especially liked his selection on the atonement as breaks down the weakness with the penal substitutionary atonement view of most Protestants while highlighting the value of the victory of God over satan, evil, sin and death. But then again I’ve been a proponent of the Christus Victor atonement view for quite some time. 🙂

Connected with the sovereignty of God and human participation topic are the issues of the atonement (i.e. what happened on the cross?) and the wrath of God. While anyone of these topics could have been a book within itself, Brad seamlessly weaves all three issues into his book while keeping the focus on Jesus and the cruciform God. I especially liked his selection on the atonement as breaks down the weakness with the penal substitutionary atonement view of most Protestants while highlighting the value of the victory of God over satan, evil, sin and death. But then again I’ve been a proponent of the Christus Victor atonement view for quite some time. 🙂