Alice was a lost soul wandering through a strange land trying to find her way back home. Along the way she stumbled upon a cat sitting on a tree branch. Initially frighten, she overcomes her fear and asks the Cat which way she ought to go. The Cat, being a bit mad, responded with perhaps the most powerful statement ever recorded, “That depends a good deal on where you want to get to.”[1] George Harrison would later paraphrased Alice’s conversation with the Cheshire Cat in the equally profound lyric, “if you don’t know where you’re going, any road will take you there.”[2]

Alice was a lost soul wandering through a strange land trying to find her way back home. Along the way she stumbled upon a cat sitting on a tree branch. Initially frighten, she overcomes her fear and asks the Cat which way she ought to go. The Cat, being a bit mad, responded with perhaps the most powerful statement ever recorded, “That depends a good deal on where you want to get to.”[1] George Harrison would later paraphrased Alice’s conversation with the Cheshire Cat in the equally profound lyric, “if you don’t know where you’re going, any road will take you there.”[2]

This advice, while originally given in the context of spatial dimensions, is equally valid in a temporal and spiritual sense. If we, the followers of Jesus, really want to find our Beloved in the darkness of the unknown, we need to first know where we are going. It may sounds strange to think about knowing where you going while embracing the mystery of the unknown. Yet, it is exactly in this paradox that we find the truth of life.

Years ago when the people of Israel were on the edge of the unknown with Jerusalem and the Temple about to be destroyed, the Creator sent the prophet Jeremiah to tell them not to worry. Rather they were to “stand at the crossroads” between the known and unknown and “ask for the ancient paths” (Jeremiah 6:16, NIV). It would be in walking down the ancient paths of those who followed the call of the Creator King that they would find rest for their souls.

The same is true for us today. We are the heirs of an ancient faith with roots back to the very beginning of time. We are not the first people to start this journey, nor will we be the last. Accordingly, we can look backwards to those who have gone ahead of us to find our way forward. As author of Hebrews reminds us, we are “surrounded” by a “great cloud of witnesses” who are cheering us on, encouraging us to finish the race set before us (Hebrews 12:1, NIV).

Philadelphia Archbishop Charles Chaput of the Roman Catholic Church once remarked that “Americans have never liked history” since the “past comes with obligations on the present, and the most cherished illusion of American life is that we can remake ourselves at will.”[3] This self-imposed historical amnesia causes us to have an unhealthy “egocentric obsession with the present”[4] as noted by Brian Zahnd. Once we embrace the concept that we are part of an ongoing story that is bigger than ourselves, then everything changes. No longer is the Christian faith about me or what I can get out of it. No longer is it just about our particular group within Christianity or our nation. Rather our eyes are opened to the bigger picture of God’s rule and reign that spans both time and space.

[1] Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (Boston: International Pocket Library, 1941), 75.

[2] George Harrison, “Any Road,” in Brainwashed, Dark Horse/EMI, 2002, compact disk.

[3] Charles Chaput, “Remembering Who We Are and the Story We Belong To” (speech, Notre Dame, Indiana, October 19, 2016), National Catholic Register, accessed October 20, 2016.

[4] Brian Zahnd, Water To Wine: Some of My Story (Spello Press, 2016), Kindle edition, 1349.

Written in the style of wisdom literature with a “delicate balance of fiction and nonfiction,”

Written in the style of wisdom literature with a “delicate balance of fiction and nonfiction,”

In the intervening years between the time of the Desert Fathers (4th and 5th century C.E.) and today (21st century C.E.), many people have sought to incorporate the concepts promoted by the humble men and women of the desert. St. Augustine (354-430 C.E.), a notable materialistic playboy before his conversion to Christianity, was especially taken with the simplicity and self-sacrifice of St. Anthony, one of the first Desert Fathers. In pondering Anthony’s life, Augustine, a young man in Milan (the capital of the Western Roman Empire at the time), came to the conclusion that “no bodily pleasure, however great it might be and whatever earthly light might shed lustre upon it, was worthy of comparison, or even of mention, beside the happiness of the life of the saints.”

In the intervening years between the time of the Desert Fathers (4th and 5th century C.E.) and today (21st century C.E.), many people have sought to incorporate the concepts promoted by the humble men and women of the desert. St. Augustine (354-430 C.E.), a notable materialistic playboy before his conversion to Christianity, was especially taken with the simplicity and self-sacrifice of St. Anthony, one of the first Desert Fathers. In pondering Anthony’s life, Augustine, a young man in Milan (the capital of the Western Roman Empire at the time), came to the conclusion that “no bodily pleasure, however great it might be and whatever earthly light might shed lustre upon it, was worthy of comparison, or even of mention, beside the happiness of the life of the saints.” St. Anthony

St. Anthony Philadelphia Archbishop Charles Chaput recently remarked that “Americans have never liked history” since the “past comes with obligations on the present, and the most cherished illusion of American life is that we can remake ourselves at will.”

Philadelphia Archbishop Charles Chaput recently remarked that “Americans have never liked history” since the “past comes with obligations on the present, and the most cherished illusion of American life is that we can remake ourselves at will.” Translated by Maxwell Staniforth, the book

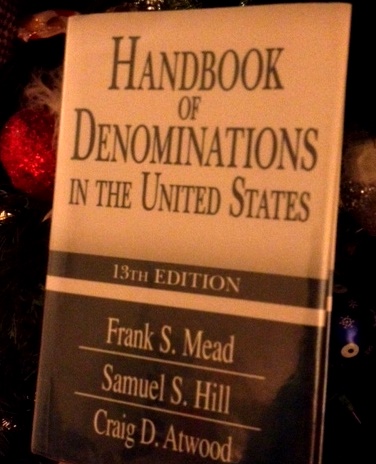

Translated by Maxwell Staniforth, the book  This Christmas I had the pleasure of reading through the

This Christmas I had the pleasure of reading through the